ClickHouse and Friends (5) Storage Engine Technology Evolution and MergeTree

In the second decade of the 21st century, I’ve been fighting on the front lines of storage engines for nearly 10 years. Driven by strong interest, I’ve barely missed a single storage-related paper on arXiv all these years.

Especially when I see papers marked “draft,” I feel the joy of a beggar hearing a “clink” sound.

Reading papers is like appraising treasures. Most are “fakes.” You need the skill to “authenticate.” Otherwise, today it’s Zhang San’s algorithm surpassing XX, tomorrow it’s Wang Er’s hardware improving YY — you’ll never keep up with the rhythm ZZ and get buried in this nutritionless technical garbage, wasting your prime years.

Back to business. The next 3 posts relate to ClickHouse’s MergeTree engine:

This post introduces the technological evolution of storage engines, deriving from “ancient” B-tree to current mainstream architectures.

The middle post will introduce MergeTree principles from storage structure, giving you a deep understanding of ClickHouse MergeTree and how to design reasonably for scientific acceleration.

The next post will start from MergeTree code, looking at how ClickHouse MergeTree implements read and write.

This is the first post, a warm-up. I believe most of this content will be unfamiliar to everyone — few people write about it.

Status

What’s the status of storage engines (transactional) in a database (DBMS)?

Much of MySQL’s commercial success comes from the InnoDB engine. Oracle acquired InnoDB several years before MySQL!

20 years ago, being able to hand-craft an ARIES (Algorithms for Recovery and Isolation Exploiting Semantics)-compliant engine was quite impressive. I believe Oracle acquired not just the InnoDB engine, but more importantly, the people. Where is the InnoDB author, and what is he doing?!

The forked MariaDB has been searching for its soul all these years. Struggling at the Server layer, it’s been declining — only able to acquire things here and there, trying its luck. The commits where TokuDB once fought remain, but these are history now.

Also, WiredTiger was acquired and used by MongoDB, playing an immeasurable role in the entire ecosystem. These engine powerplants are critical to a car.

Someone asked: it’s 2020 — is developing a storage engine still so hard? Not hard, but what you build might not be as good as RocksDB?!

As everyone can see, many distributed storage engines are developed based on RocksDB — a wise choice in the short term.

From an engineering perspective, there’s so much to polish in an ACID engine. It’s full of manpower, money, and patience consumption. One possibility is stopping halfway through development (like nessDB). Another possibility is realizing halfway through that it looks just like XX. WTF.

Of course, this isn’t encouraging everyone to build products based on RocksDB. Rather, choose based on your situation.

B-tree

First, a respectful address: sir. This sir is 50 years old and currently supports half of the database industry.

Unchanged for 50 years, and people still have no intention of changing it. This sir is impressive!

To judge an algorithm’s merits, there’s a school called IO Complexity Analysis. Simple deduction reveals truth or falsehood.

Let’s use this method to analyze B-tree’s (traditional b-tree) IO complexity. Read and write IOs are clear at a glance — truly understanding why reads are fast, writes are slow, and how to optimize.

For pleasant reading, this article won’t derive any formulas. How can complexity analysis have no formulas!

Read IO Analysis

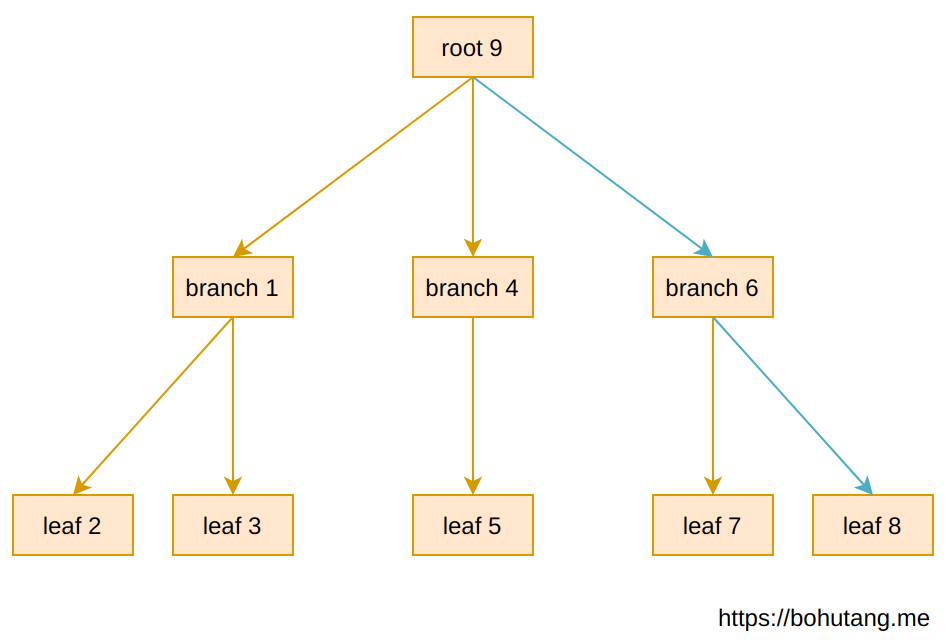

Here’s a 3-level B-tree. Each square represents a page, numbers represent page IDs.

The above B-tree structure is a memory representation. If we want to read a record on leaf-8, the read-path is shown by the blue arrow:

root-9 –> branch-6 –> leaf-8

Below is the B-tree’s storage form on disk. The meta page is the starting point:

So the total random IO for reading (assuming no page cache in memory and pages are stored randomly) is (blue arrows):

1(meta-10)IO + 1(root-9)IO + 1(branch-6)IO + 1(leaf-8)IO = 4 IOs. Ignoring the always-cached meta and root, that’s 2 random IOs.

If disk seek is 1ms, read latency is 2ms.

Through deduction, you’ll find B-tree is a Read-Optimized data structure. Whether LSM-tree or Fractal-tree, reads can only be slower than it due to Read Amplification issues.

Storage engine algorithms are ever-changing, but most are struggling with Write-Optimized. Even a constant-factor optimization is a breakthrough. Since Fractal-tree’s breakthrough, there’s been no successor!

Write IO Analysis

Now write a record to leaf-8.

You can see each write requires reading first, as shown by the blue path above.

Assuming this write causes both root and branch to change, this in-place update reflected on disk is:

Basically 2 read IOs and 2 write IOs + WAL fsync, roughly 4 random IOs.

Through analysis, B-tree is not friendly to writes. Many random IOs, and in-place updates must add a page-level WAL to ensure rollback on failure. Literally deadly.

Write-Optimized B-tree

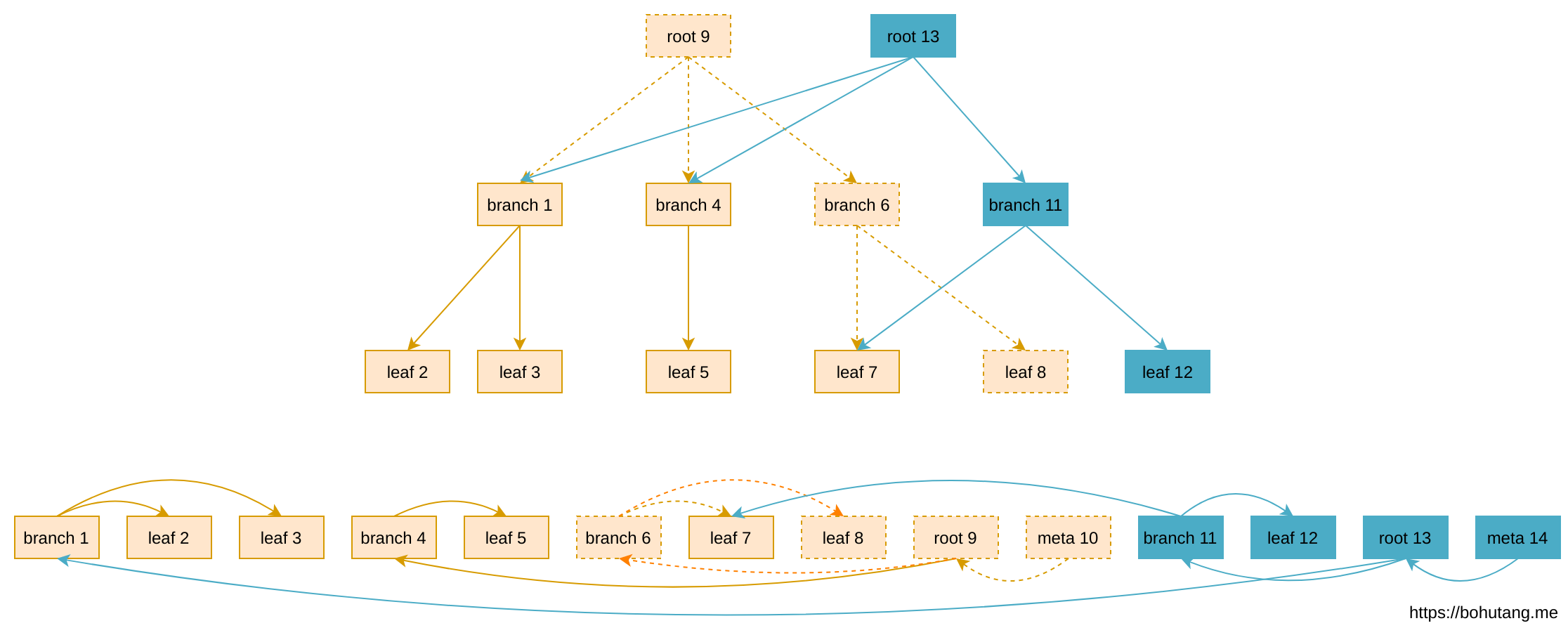

Speaking of write optimization, in the HDD era, everyone’s direction was basically converting random IO to sequential IO, fully leveraging disk mechanical advantages. Thus appeared a kind of Append-only B-tree:

- Updates generate new pages (blue)

- Pages are appended to file end when written back to disk

- No need for page WAL, data doesn’t overwrite. Has Write Amplification issues, needs hole reuse mechanism

Append-only B-tree saves 2 random IOs during write-back, converting to constant-level 1 sequential IO. Write performance greatly improves. Summary:

Random becomes sequential, space trades time

This is also the core idea of write-optimized algorithms like LSM-tree and Fractal-tree — just different implementation mechanisms.

LSM-trees

With LevelDB’s advent, LSM-tree gradually became known.

LSM-tree is more of an idea, blurring the seriousness of “tree” in B-tree by organizing files into a looser tree.

Here I won’t discuss whether a specific LSM-tree is Leveled or Size-tiered — just the general idea.

Write

First write to memory C0

Background threads merge according to rules (Leveled/Sized): C0 –> C1, C1 –> C2 … CL

Return after writing to C0, IO goes to background Merge process

Each Merge is a pain point — big movements stutter, small movements perform poorly, data flow direction in each Merge is unclear

Write amplification issue

Read

- Read C0

- Read C1 .. CL

- Merge records and return

- Read amplification issue

Fractal-tree

Finally evolved to the “ultimate” optimization (currently the most advanced index algorithm): Fractal-tree.

It’s based on Append-only B-tree, adding a message buffer to each branch node as a buffer. Can be seen as a perfect fusion of LSM-tree and Append-only B-tree.

Compared to LSM-tree, its advantage is very clear:

Merge is more orderly, data flow is very clear, eliminating Merge jitter issues. The compaction anti-jitter solution everyone’s been looking for has always existed!

This high-tech is currently only used by TokuDB. This algorithm could be a new chapter. Not detailed here. If interested, refer to the prototype implementation nessDB.

Cache-oblivious

This term is unfamiliar to most people, but don’t be afraid.

In storage engines, there’s a very, very important data structure responsible for maintaining page data order. For example, how to quickly locate the record I want in a page.

LevelDB uses skiplist, but most engines use a sorted array like [1, 2, 3, … 100], then use binary search.

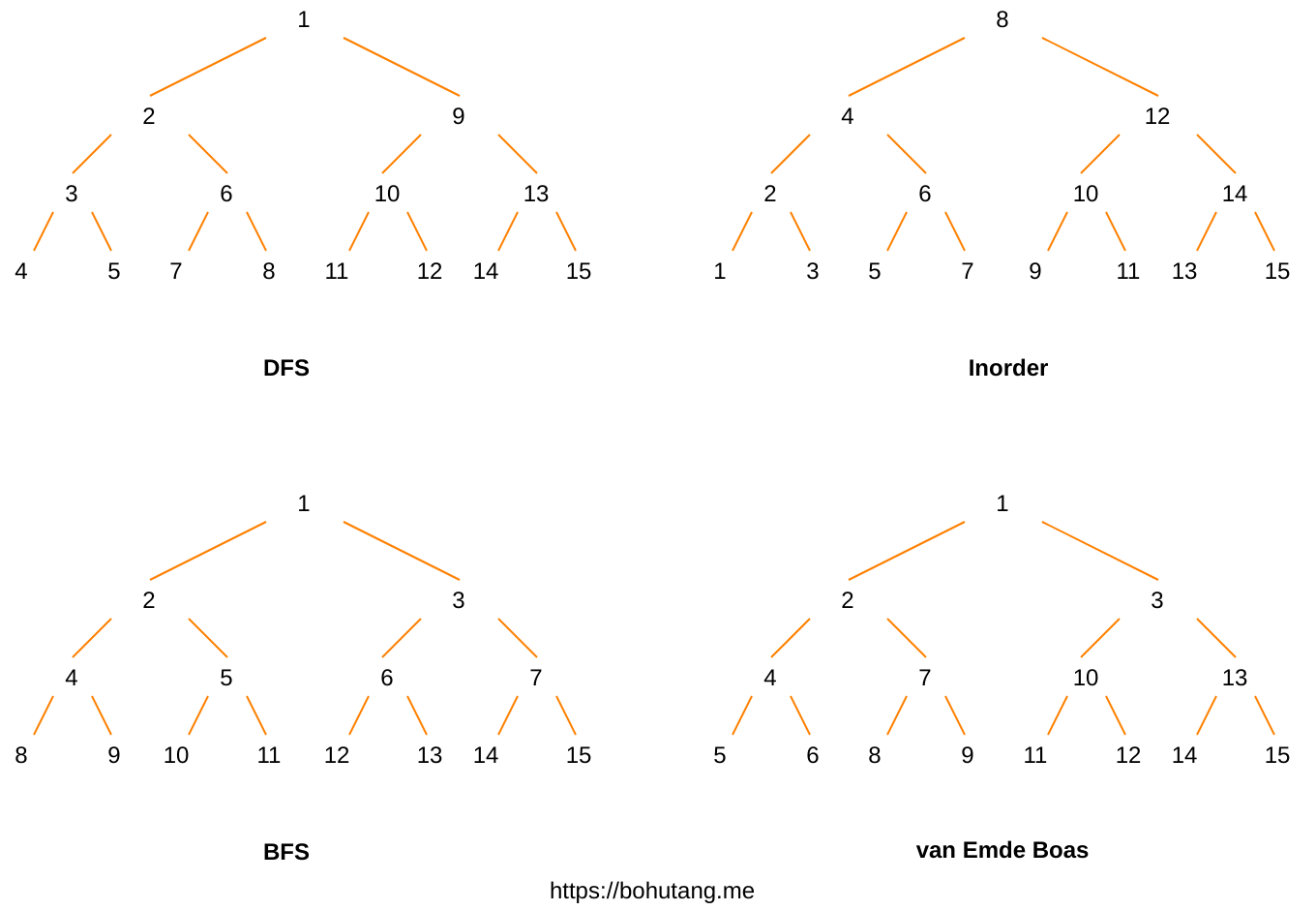

About 10 years ago, a kernel developer published <You’re Doing It Wrong>. This little article discussed something interesting:

Data organization form greatly affects performance because CPUs have cache lines.

Setting this article aside, let’s look at a “divine” diagram:

These are 4 layout representations of a binary-tree. Which layout is most friendly to CPU cache lines?

Maybe you’ve already guessed — van Emde Boas, abbreviated vEB.

Because its adjacent data is stored “clustered,” point-query and range-query cache lines can be maximally shared. Skiplist is very unfriendly to cache lines. Can be even faster!

For cache oblivious data structures, here’s a simple prototype implementation: omt

B-tree Optimization Magic Quadrant

Write-optimized algorithms evolved from native B-tree to Append-only B-tree (representative work: LMDB), to LSM-tree (LevelDB/RocksDB, etc.), and finally to the currently most advanced Fractal-tree (TokuDB).

These algorithms took many years to implement and be recognized in engineering. Developing a storage engine lacks not algorithms but the ability to “appraise treasures.” This “treasure” may have been lying around for decades.

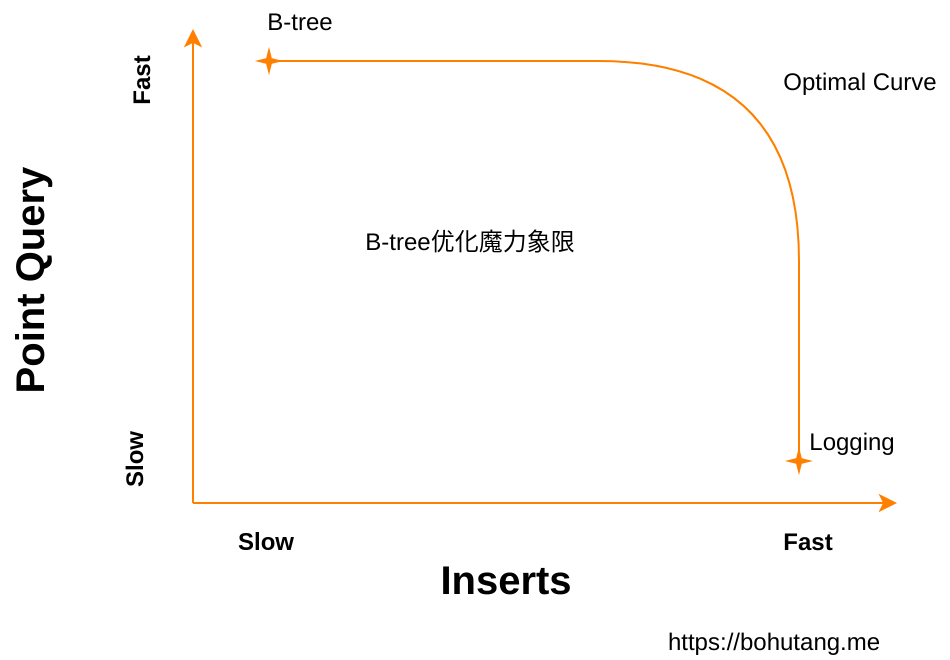

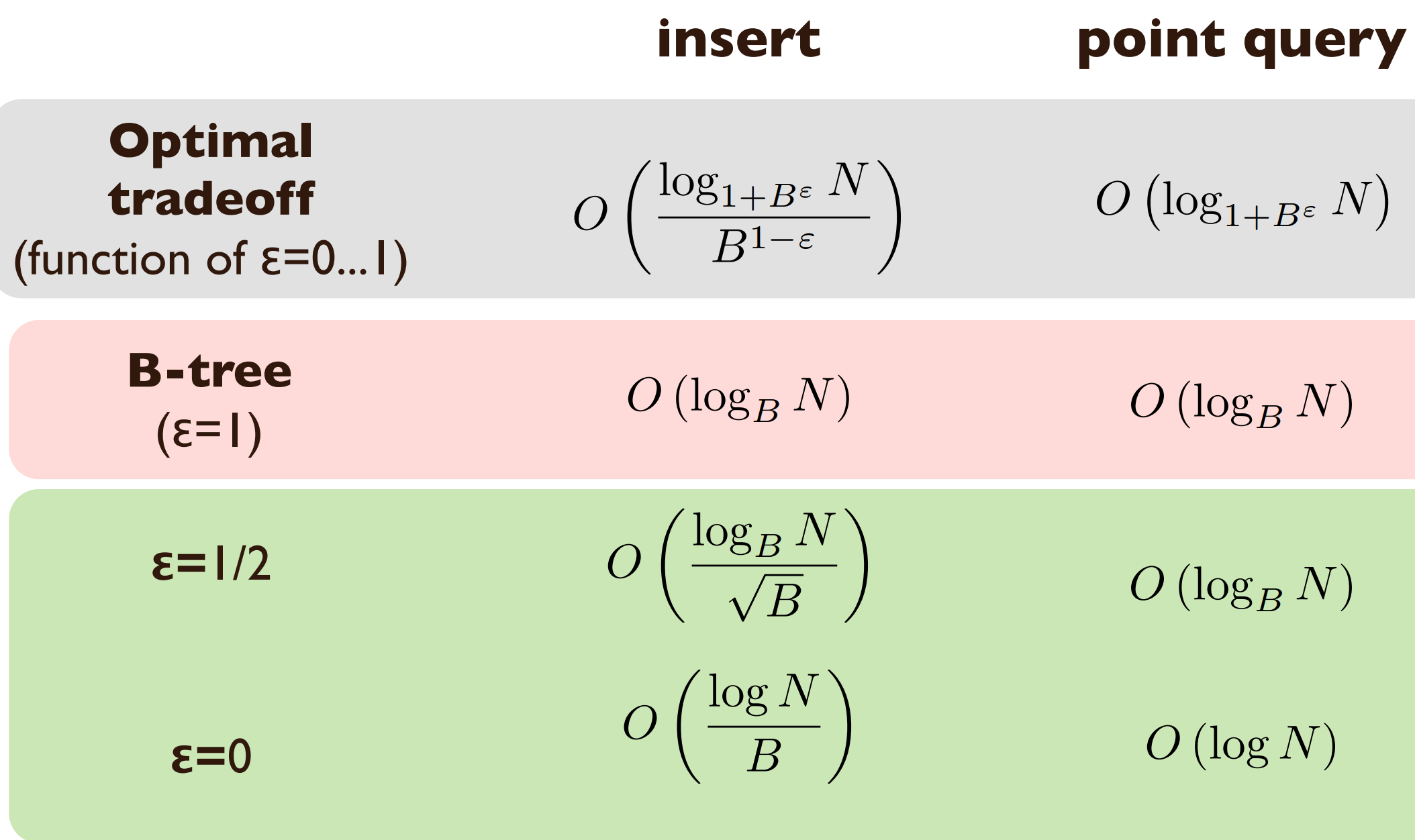

Actually, “scientists” have already summarized a B-tree optimization magic quadrant:

The X-axis is write performance, Y-axis is read performance. B-tree and Logging data structures are distributed at two extremes of the curve.

B-tree has very good read performance but poor write performance.

Logging has very good write performance but poor read performance (imagine we append data to file end each write — very fast? But reading…).

Between them is an Optimal Curve.

On this curve, you can increase/decrease a constant (1-epsilon) to combine read and write optimizations. LSM-tree/Fractal-tree are both on this curve.

Summary

This article mainly discusses the technological evolution of transactional engines, including IO complexity analysis. Actually, this analysis is based on a DAM (Disk Access Machine) model, which I won’t expand on here.

What problem does this model solve?

If engineering involves hardware hierarchy, like Disk / Memory / CPU, where data is on Disk, read (in blocks) to Memory, search and compute (cache-line) on CPU,

and performance differences between different media are huge, how can we make overall performance more optimal?

Combined with today’s hardware, this model still applies.

Finally, back to ClickHouse’s MergeTree engine. It only uses part of the optimizations in this article. Implementation is relatively concise and efficient. After all, no transactions means no psychological burden when coding.

Random becomes sequential, space trades time. For MergeTree principles, tune in next time.

References

[1] Cache-Oblivious Data Structures

[2] Data Structures and Algorithms for Big Databases

[3] The buffer tree: A new technique for optimal I/O-algorithms

[4] how the append-only btree works

[5] 写优化的数据结构(1):AOF和b-tree之间

[6] 写优化的数据结构(2):buffered tree

[7] 存储引擎数据结构优化(1):cpu bound

[8] 存储引擎数据结构优化(2):io bound

[9] nessDB

[10] omt